Nazi concentration and extermination camps

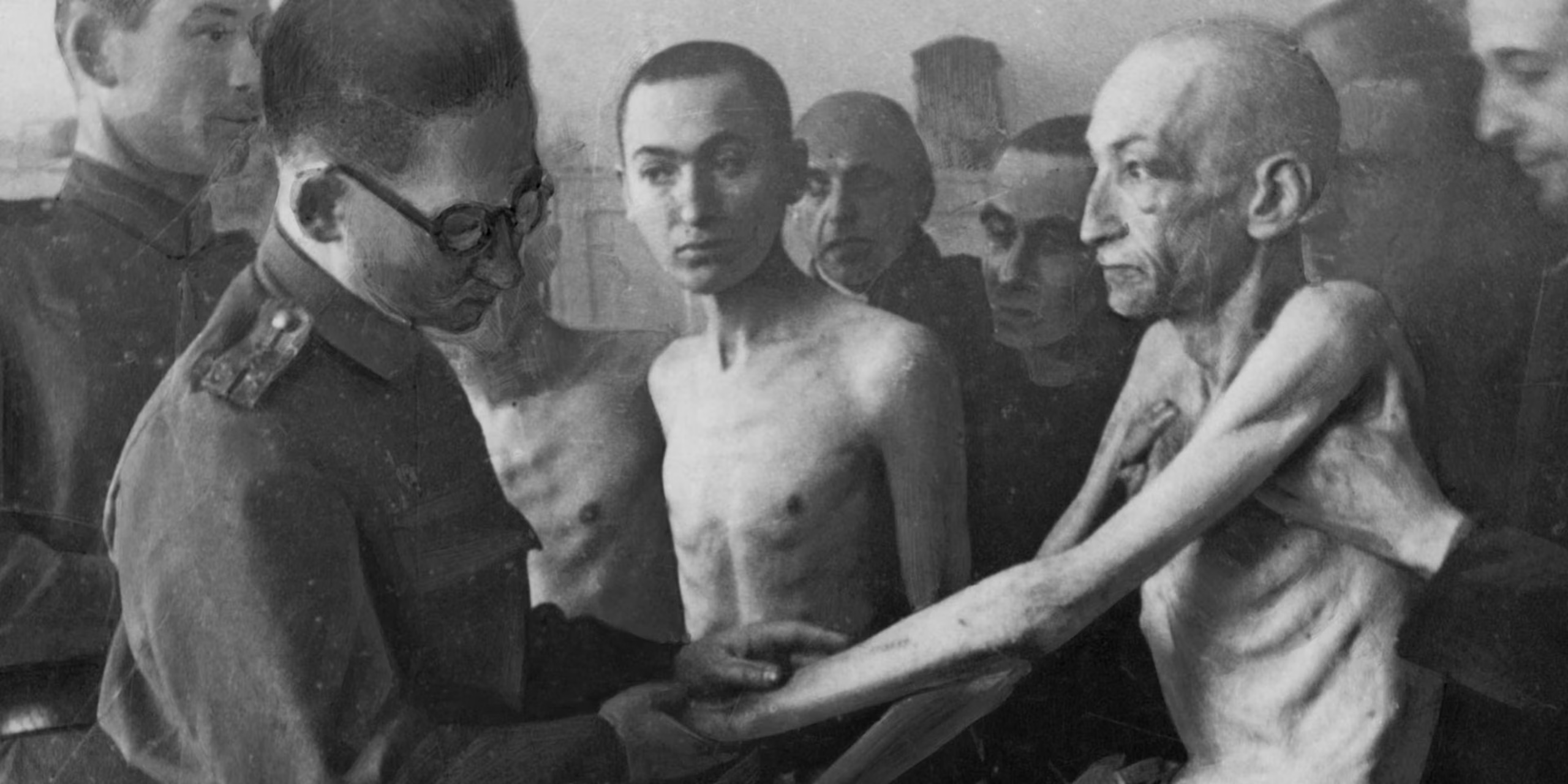

In January 1945, as the Red Army advanced westward into Nazi-occupied Poland, Soviet troops arrived at the gates of Auschwitz, the largest and most notorious of the Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

What they found was a scene of unimaginable horror: thousands of emaciated prisoners barely clinging to life, evidence of mass murder, and a haunting silence that echoed the absence of over a million lives lost. Among the first responders were Red Army doctors, tasked with the grim but vital duty of assessing and treating survivors who had endured years of starvation, abuse, and disease .

In one powerful image, a Soviet military doctor leans in to examine a newly liberated prisoner—his expression marked by a mixture of compassion and disbelief. The survivor, frail and skeletal, is wrapped in a thin blanket, his eyes hollow with exhaustion but flickering with a glimmer of hope. For the Soviet doctor, trained in battlefield medicine, this was a different kind of war wound—a moral and human wound inflicted by systematic cruelty, requiring not only medical intervention but a reckoning with humanity itself.

This moment, frozen in time, reflects both devastation and resilience. The liberation of Auschwitz marked the beginning of healing for those who had lived through unspeakable suffering, though the scars—both visible and hidden—would remain. The image of a Red Army doctor caring for a survivor underscores the shift from genocide to restoration, from silence to testimony. It stands as a solemn reminder of what was lost, and of the responsibility to remember .